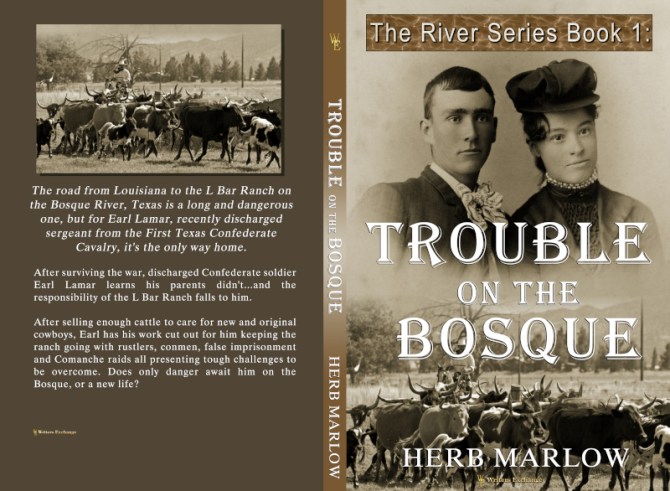

The River Series, Book 1: Trouble on the Bosque by Herb Marlow

The road from Louisiana to the L Bar Ranch on the Bosque River, Texas is a long and dangerous one, but for Earl Lamar, recently discharged sergeant from the First Texas Confederate Cavalry, it’s the only way home.

After surviving the war, discharged Confederate soldier Earl Lamar learns his parents didn’t…and the responsibility of the L Bar Ranch falls to him.

After selling enough cattle to care for the original cowboys and new families, the Esperanzas and the Roses along with cook Henry Spooner, Earl has his work cut out for him keeping the ranch going with rustlers, conmen, false imprisonment and Comanche raids all presenting tough challenges to be overcome. When Earl falls in love and he and Gloria find themselves expecting their first child, he begins to hope that maybe, just maybe, a new life awaits him on the Bosque.

GENRE: Western Word Count: 66,549

| Amazon | Apple Books | Google Play | Barnes and Noble | Kobo | Scribd | Smashwords | Angus & Robertson Print |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(ebooks are available from all sites, and print is available from Amazon, Barnes and Noble and some from Angus and Robertson)

Continue the series:

![]()

Chapter One

The horse I was riding was a sorry looking beast, but at least it was a horse. I had found him wandering along a creek in Louisiana just south of Shreveport still saddled and bridled, but with broken reins, and he wasn’t hard to catch.

Well, I’d walked most of the way from Alexandria after General Bagby surrendered us on May 26, 1865, and even a ewe-necked bag of skin over ribs looked mighty fine to me. Trouble was, I didn’t think stealing a horse would make me very popular with folks in the area, so I decided that maybe I should look for the owner.

After catching the horse I rigged some reins out of a bit of rope I carried and decided to ride him. The saddle was a postage stamp affair, not the big-horned Texas saddle I was used to, or the military saddle I’d been riding for three years, but once I got the stirrups lowered for my long legs, I climbed aboard, slinging my pack and rifle scabbard from my shoulders.

From how short the stirrups had been I figured the owner of the horse couldn’t have been real tall, maybe a kid, and I found the boy when I got up through the brush onto an embankment. He was about ten, and he was sitting on the edge of the road crying. He looked up when I came out of the brush, and got to his feet. “Oh, you found him,” he said with relief.

“Is this your horse, son?”

“Yes, sir. Well, not really, but I had him tied to a tree and he got loose. If I don’t get him back, Uncle Charlie will skin me alive.”

I got down and helped the boy reset the stirrups, but he made no move to get back in the saddle. “You been in the war?” he asked.

“Yep, just trying to get back home.”

“Where you from?” he wanted to know.

“Texas.”

The boy’s eyes grew big. “I’ve always wanted to go to Texas. Are you a cowboy?”

We were slowly walking up a well-traveled path through big trees. “Well, I suppose. My people own a ranch out in Bosque County. If I once get back there, I don’t plan to ever walk more than twenty feet again.”

“Was you in the calvary?”

“Yep, but you pronounce it cavalry. I was in the 1st Texas Cavalry. Trouble was, I wasn’t an officer, and when the Yankees took our surrender, they made us enlisted men give up our horses.”

The boy was quiet for a bit and then said in a low voice, “Bet you don’t like Yankees much, huh!”

“Not much, although now that the war’s over, I don’t intend to be around many of them.”

The boy stopped walking and looked at me. “If you don’t want to meet a Yankee, y’all better not come home with me, mister. My Uncle Charlie was a Yankee in Tennessee, and he just got home a week ago. My pa and older brother both died in the war on our side, so Uncle Charlie’s taken over the farm. Says me and my mom will do as he says or he’ll whip us. He thinks because he was a Yankee soldier and they won the war he can do whatever he wants to, and I guess he’s right.”

I thought about this for a minute. Sounded like Uncle Charlie wanted to make slaves out of his own kin. Maybe he hadn’t heard that Lincoln freed all the slaves. “Is he your mother’s brother?”

“Nope. He ain’t my father’s brother either. My name’s Jubal Haynes, and his is Charlie Walters. He is some kin of ours, but not close. He makes me call him Uncle Charlie, though. This here is his horse, or at least the one he came back on.”

Now, I never had held with slavery. Maybe because out our way we didn’t own any slaves, and we all worked like slaves ourselves. Or maybe because it just went against my grain for one man to own another. And to think about this Charlie taking over a farm and making slaves out of a woman and her son just because they couldn’t stop him made my hackles rise. I held my right hand out to the boy. “I’m Earl Lamar, and I think I’d like to meet your Uncle Charlie.”

I guess the grin I gave him reassured Jubal, for he smiled in return. “Well, Mister Lamar, I reckon I’d like to introduce you to him,” and we laughed together, and then walked on in silence.

As we rounded a bend in the road, I could see a substantial-looking two-story house up ahead with a half circle drive lined with huge live oaks in front. Weeds nearly choked the drive now, and the house’s white paint had turned a dingy gray, but I could see that the place had been real nice at one time.

Jubal led the horse down a narrow lane to one side of the house and into the barnyard out back. There was a stable along one side of a hollow square, a series of cattle pens along another, what appeared to be a smoke house on the north side, and the house on the west. In back of the house I could see some small buildings that might have been slave quarters. Like the house, everything was run down now, but it looked like somebody had built carefully and strong at one time.

Jubal stood beside me as the back door of the house opened and a big, burly man in his thirties appeared. He was bearded and his black hair grew long down his back. He was dressed in a dirty undershirt tucked into blue trousers with a red stripe down the side of each leg. That meant artillery, though somehow this man didn’t fit the picture of the Yankee artillerymen I’d seen in the war.

“You fool kid!” the man shouted. “Where you been with that horse? I told you to take him down by the creek and let him graze, but you been gone long enough to have rode into Shreveport.” He came storming down the steps from a small porch and stomped on across the barnyard unbuckling his belt. “I’ll learn you a thing or two!”

This must be Uncle Charlie. Jubal slid behind me for protection, and Charlie tried to hit him with the heavy belt buckle. I grabbed the belt and pulled hard enough to get it out of his hands and said, “Whoa there, mister. No need to get all worked up.”

He drew back and looked at me. “Well, looky here. A Johnny Reb tellin’ me what to do on my own place. I don’t know who you are, reb, but you better just get on down the road or I’ll have the law on you. I want to see your backside like I saw so many of you gray backs run in the war.”

He looked me over real careful and I know he didn’t see much. My clothes were ragged and dirty, and my six-foot frame was lean, mostly because we hadn’t had much to eat in the last year. With brown hair, hacked off with a knife, and my face covered with curly whiskers, I didn’t look like much. My old black hat with the broken brim shaded my brown eyes. I was sure he couldn’t see the Army Colt .36 I had stuck in my waistband under my jacket, so I looked unarmed, too. My pack was slung behind me on one shoulder, and the rifle scabbard with it. That scabbard had a flap over the butt of the stock, and since it was kind of long and flat, it didn’t look like what it was.

I doubted if Uncle Charlie’d ever been close enough to see a Confederate soldier’s back or front during the war from the look of the fat around his middle, so I just grinned at him. “Oh, I doubt if you’ve seen many rebels runnin’, Yankee. Kind of hard to see when you’re runnin’ the other way yourself, ain’t it?”

That touched a nerve. The man backed up and his face went red. I thought he might try to hit me, but he wasn’t made of that kind of stuff. “Well, I’m facing a reb right now, and I ain’t runnin’!” He reached into his right hip pocket and pulled out a gun. As he whipped it up to waist level and eared back the hammer, I could see that he was bound to shoot me, so I pulled out my Colt and let him have it.

Uncle Charlie was flung back like he’d been hit by a mule, and he dropped straight down on his back, gave a loud sigh, and didn’t move again. It was suddenly very quiet in the barnyard.

Jubal stirred behind me and said, “Did you kill him?”

I walked on over and nudged Charlie’s gun away from his hand and looked down at him. His mouth was open showing yellow teeth, and his eyes were closed. I’d seen a lot of dead men in the last two years, and this man wasn’t one of them. There was a long wound on the side of his head that was still bleeding. “No, he’s not dead, Jubal. But he’s sure goin’ to have a bad headache.”

I suppose I should have felt sorry about shooting the man, but somehow I just couldn’t. From what the boy told me, and what I’d seen with my own eyes, Uncle Charlie wouldn’t have been missed by anyone if he had died.

The screen on the back door of the house banged and a woman stood on the stoop. “Jubal,” she called in a tremulous voice. “Are you all right?”

Jubal ran to the porch and hugged the woman, and I could hear him murmur to her. The two came down the steps together and walked right up to me.

I’d shoved the Colt back into my waistband, and when the woman held out her hand I shook it. The hand was small, but it wasn’t smooth. There was a roughness about it that told me she had been doing hard work. “Welcome, sir. I’m Madge Haynes, and I believe you’ve done us a great favor.” She spoke like a lady, and I could see she was one.

Well, I pulled my old beat up hat off and nodded to her. She hadn’t looked at Uncle Charlie. “I’m Earl Lamar,” I said. “Sorry about the shootin’, ma’am, but he was fixin’ to pull the trigger on that pistol.”

Without a change in expression tears began to slide down Mrs. Haynes’ face. “Oh, Mr. Lamar, you don’t know how glad I am that you shot that man. You just don’t know.” And she buried her head in her hands and began to sob. Jubal hugged her, and I stood there like a bump on a log. Crying women were way out of my experience, and I figured the best thing I could do was nothing. Turned out I was right.